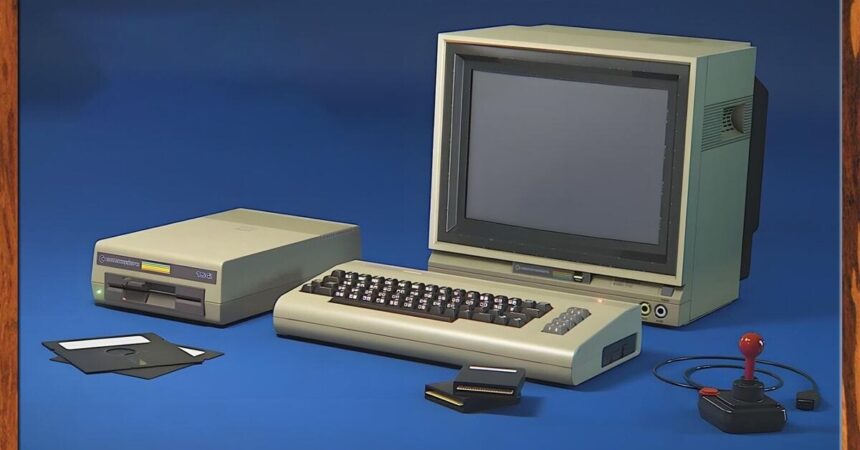

The thriller unfolds at the very core of “A Historical Past of the Commodore 64”, Jesper Juul’s captivating exploration into the origins of this iconic computer.

What’s behind the Commodore 64’s surprising absence from online gaming archives, a device that sold over 17 million units, its immense popularity warranting more recognition within the gaming community?

Few would bother to pose such a question without any genuine curiosity. In his e-book, Jesper Juul tackles this query with unwavering dedication, leveraging the methodologies of media archaeology to excavate the historical past of video video games and conclusively demonstrate how—indeed, remarkably so—historians and writers have overlooked the profound impact of the C64 on the evolution of the medium.

Time and again, Juul highlights instances where histories of video games hastily gloss over the Commodore 64’s significance, rushing instead to condense the narrative into a truncated chronicle. As the story unfolds, the narrative’s foundation is laid by tracing the evolution of pinball machines into arcade machines, ultimately culminating in the rise of Magnavox and Atari, a trajectory that came to a head in 1983. The legend unfolds: following the collapse of the home computer market, Nintendo spearheaded a revival in the industry with the introduction of the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), effectively marking the beginning of the modern era for video game consoles.

Juul contends that the prevailing narrative surrounding the history of video games, which centers on a supposed “crash,” inadvertently overlooks crucial linkages in the timeline.

In an email exchange with me, Juul emphasized that as a researcher or journalist, it’s often easier to recycle a well-known narrative when establishing context, citing that the familiarity can serve as a useful starting point. In the United States, this development eventually became synonymous with ‘the crash’ of 1983, a phenomenon almost exclusively limited to the American market, which also overlooked the thriving home computer industry in North America. Throughout the 1980s, Digital Arts and Activision collaborated on producing iconic Commodore 64 video games.

Despite being often condensed into a simplistic narrative, the early history of video games has largely been reduced to a shorthand: “The crash, and then came Nintendo,” suggests Juul. “That’s simply life for you.”

Despite being a relic of the past, the Commodore 64’s vast library of video games remains a fascinating phenomenon, with over 12 million households once owning the iconic computer.

Despite the prevalence of piracy on the Commodore 64, it is impossible to determine which video games were most popular among C64 enthusiasts solely by examining gross sales charts. Despite this challenge, Juul offers a viable solution, as exemplified by a UK-based journal that regularly surveys its readers to identify their top 5 video games each month.

Through meticulous archival research, Juul successfully created a historical chart akin to Billboard’s Hot 100, showcasing the video games that spent the most time atop the GAMES TOP 30 chart.

While many anticipated classics are indeed present (), some notable absences do stand out (). Initially released on the Commodore 64, despite its enduring popularity, it mysteriously omitted from the charts. In what ways did SimCity, its precursor, differ from the first game designed by renowned creator Will Wright, which was published to widespread acclaim?

The response to this notion is significantly influenced by the striking discovery that the Commodore 64 possessed the largest collection of commercially released, printed video game manuals of any platform predating MS-DOS throughout the 1990s. According to Juul’s meticulous research, more than 5,000 video games were released on the Commodore 64 (C64) during its 12-year run.

From “Let’s Fail!” by Jesper Juul, reprinted with permission from the author.

Here’s the improved text:

Having exhaustively reviewed numerous Commodore 64 video games for the book, I approached Juul with a query about his recommendations for newcomers to the platform.

JESPER JUUL: Very arduous query! I’d say:

While I’m usually keen to suggest novel activities, attempting to get drunk or getting drunk without a doubt isn’t advisable.

Without suggesting that it’s an effortless revisit of the Commodore 64 during its prime, your outline might give the impression that this is a straightforward look back at the C64 era; however, the book is actually much more peculiar than that?

The animating concept building this ebook is the notion, a thought derived from media archaeology, which primarily contends that actual technologies are consistently shaped by fictional conceptions of how technology could work.

With a VR headset strapped to my face, it’s tempting to imagine myself as a pioneer in a future where virtual environments have become an integral part of daily life – yet, I’m forced to acknowledge that this immersive experience is usually short-lived, lasting only around 10 minutes before the headset is removed. While imaginaries often set unrealistic goals for machines, the harmonious convergence of precision and imagination enables the creation of innovative systems. The intersection of imaginary and precise media machines facilitates seamless transitions. . . might be nearly seamless.”1

I interpret the term “imaginary” to encompass any conceptualized notion of a knowledge’s functionality, role, or significance. The complexities of human-computer interaction are influenced by imaginative constructs.

I’m thoroughly captivated by this idea and the VR application developed by Juul is perfectly suited to bring it to life. The VR/AR industry has largely been driven by an elusive vision conceived over a decade ago.

“In an era of immersive gaming experiences, imaginaries have become a staple in modern video games,” I was told by Juul. You’ll be able to visualise this concept in practice, much like the innovative integration of hardware seen in the Xbox One and Kinect, where Microsoft envisioned the console as a central hub for entertainment, enabling users to control their TV experience with voice commands and intuitive gestures, mirroring the seamless fusion of technology and convenience. It seemed like a sound business strategy, but unfortunately, nobody seemed to care about its implementation, which meant the envisioned future never materialized.

The text examines the notion’s underlying dynamics, delving into the fantastical constructs that have shaped the public’s perception of the Commodore 64 throughout its storied history.

Juul dissects the Commodore 64’s (C64) historical narrative into five distinct epochs, leveraging the framework of evolving imaginaries to illuminate how the public’s perception of this iconic computer evolved over time.

While every chapter has its own unique charm, Chapter Three stands out for its thrilling account of how hackers exploited the Commodore 64’s vulnerabilities, making it the most captivating read. Juul’s direct participation in Denmark’s vibrant “demoparty” culture is meticulously documented, accompanied by a selection of amusing on-site photographs that offer a glimpse into his hands-on involvement.

While technically proficient and showcasing reverence for its components, Juul’s true uniqueness lies in its innovative historical reporting, enthusiastic game discussions, and captivating visual storytelling through photos of unbridled Danish hacking events. As he delivers insights amidst the chaos, he surprises you with intriguing nuggets of news reporting.

I wholeheartedly endorse. This innovative work is a unique corrective to traditional historical accounts, boasting a distinct identity of its own.

Before departing, I’d like to highlight an unusual connection I uncovered while investigating a peculiar anecdote in the book mentioned by Juul – a fascinating tale that led me down a winding path of discovery.

Early in the ebook, a particularly astonishing passage emerges as Juul nonchalantly alludes to several business ventures that flourished during the Commodore era.

“I will simply quote the eBook directly.”

What if Commodore’s trajectory had been altered by pivotal decisions that would have reshaped the course of history? In 1976, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak attempted to sell their Apple II personal computer to Commodore for a substantial sum, reportedly “a couple of hundred thousand dollars”, only to be rebuffed. The Commodore executive team rejected the opportunity to distribute VisiCalc, the pioneering spreadsheet software. Given Commodore’s established relationships in Japan and the fact that several early VIC-20 games were developed by Japanese firm HAL Laboratory – whose future leader was none other than Nintendo’s Satoru Iwata – it seemed only logical for Commodore to license Nintendo’s popular video games. Despite reaching an agreement with Nintendo in 1982, Product Supervisor Michael Tomczyk was left frustrated when Commodore’s Chairman, Jack Tramiel, reneged on the deal at the last minute without explanation? Tomczyk has openly expressed his discontent with Tramiel’s compromise, citing a reluctance to provoke or offend Bally, whose notorious reputation Tomczyk verifies: “Some individuals claim that there were some influential figures operating at Bally/Halfway, and I can confirm that.” In response, Nintendo explored options with Atari and Coleco as potential alternatives. While it’s natural to second-guess such decisions, we can’t know how alternative choices might have unfolded in retrospect.

I discovered this concept and thoughtfully continued exploring. Tomczyk’s assertion suggests that Commodore’s decision to abandon its pursuit of Nintendo, likely with far-reaching consequences for the online game industry’s trajectory, stemmed from the personal motivations of CEO Jack Tramiel. This tantalizing claim alone warrants an entire tome dedicated to exploring the intricacies of this pivotal moment in gaming history.

For decades, investigative reporters have scrutinized the alleged ties between the notorious Genovese crime family and Bally/Halfway, which held the exclusive US distribution rights for the blockbuster films “The Godfather” and “The Godfather: Part II”. The deal was negotiated with Tramiel, who had secured an agreement with Bally/Halfway to market their video games. It’s hardly a stretch to assume that Tramiel would have been loath to take an action that would invite the wrath of Bally/Halfway and its influential supporters.

Tramiel, a Holocaust survivor who rose to legendary status in the business world, passed away in 2012, while Michael Tomczyk, now 76 years old, remains active in the technology industry. I contacted Tomczyk and we connected via phone call.

When Tomczyk learned about the initial agreement between Commodore’s workforce and Bally/Halfway, he confirmed that it was current at that time. The agreement stipulated that all video game intellectual property from Bally/Halfway would be licensed, excluding which had previously been granted to Atari.

“My role involved presenting the VIC-202 report”2 Following the discussions, the technology will successfully render video games. He characterizes the adoption process as remarkably swift and efficient. There was no contractual agreement in reality. It was a letter settlement. As we exited the assembly, Jack exclaimed, ‘That’s the swiftest and most impressive business deal I’ve ever negotiated.’

Tomczyk asserts that the absence of a comprehensive contract was deemed inconsequential. “Though some claim a connection between Bally/Halfway and organized crime, I’ll refrain from commenting on the matter.” Despite this, the people there had a peculiar attitude towards contracts – they didn’t worry about them. While considering its adoption.

Shortly after, Tomczyk reportedly attempted to negotiate a deal with Nintendo that mirrored the agreement he had just reached with Sega. As he recounted his tale to me:

I successfully negotiated a deal to acquire and port Nintendo’s entire library of video games onto Commodore computer systems. After obtaining Jack’s prior approval, I formally executed the agreement as promised. I extended an invitation to Nintendo’s Vice President to revisit our offices in California, with the aim of finalizing the agreement, but unfortunately, he cannot recall the individual’s name.

He arrived, scrutinized the agreement, and formally sealed the deal. When I took the document to Jack’s office to gain his input, he scrutinized it with a poker face before revealing that he had changed his mind, saying “I’m sorry, Michael, I’ve revised my thinking.” I was taken aback, so I asked him to clarify, and he reiterated, “I’ve revised my thinking.” “I have no desire to take on the responsibility of caring for Nintendo.”

According to Tomczyk, he speculates that Tramiel’s reluctance to proceed with the agreement stemmed from his concern about offending Bally. Despite the risks, Jack confessed to being unafraid of the mob. “He was completely fearless. Bally, the leading arcade game developer, uniquely licensed its titles to Commodore, whereas it would have been unwise to compromise on its competitive edge by doing so with Nintendo. It was the notion that had been the focal point of Jack’s determination.

Although time presented a significant opportunity for acceptance;

I’m going to lose a ton of face in Japan? With a mix of candor and diplomacy, Jack shared the outcome: “I’ve negotiated in good faith, but he’s waiting for you in the next room.” Jack then instructed me to break the news: “Tell him we’re pulling out of the deal.” Reluctantly, I retreated with my head hung low to inform the Nintendo Vice President that Jack had opted to back away from the agreement.

How did the VP react? I requested.

“I relayed the details of the situation to him and extended a sincere apology.” He was very cool. He’s Japanese! With an air of serenity, he demonstrated remarkable composure in the face of adversity. He accepted it. After that, we hardly exchanged words; then he departed.

The Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), known as the Famicom in Japan, debuted 12 months after its release. Its CPU was a customized iteration of the same MOS Technology 6502 processor used in Commodore’s iconic VIC-20, an early personal computer pioneer. Historically speaking, events often seem predetermined. It’s typical to locate where the path diverged.