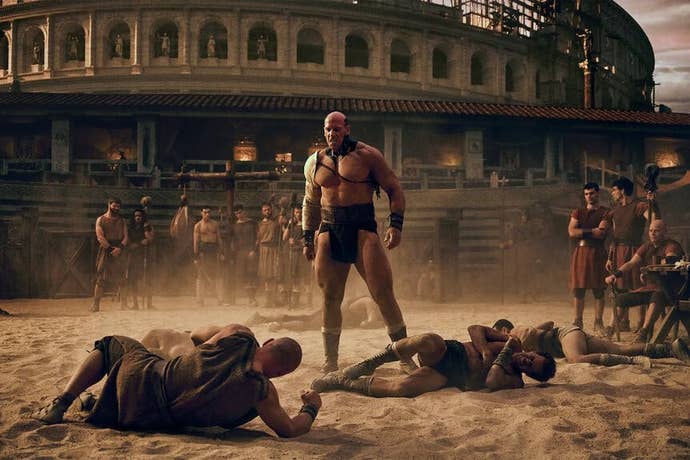

Not too long ago, I was delighted to join the esteemed pantheon of Historic Rome’s most iconic dramas, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Spartacus and Gladiator, yet refreshingly, I had the privilege of telling the story of a much less celebrated dynasty than the Julio-Claudians – that of the Flavians. Through Rome’s vibrant public spectacles – the thrill of chariot racing, the bloodlust of gladiatorial combat, and the intricate networks of power brokers who fuel their fortunes – their tale is masterfully woven. The Flavian dynasty’s tenure was profoundly shaped by its delicate balancing act with public perception. As you immerse yourself in the vibrant digital arena, the thrill of Circus Maximus comes alive, with a richly populated scene unfolding before your eyes, accompanied by a pulse-pounding, adrenaline-fueled action that electrifies every moment.

Roland Emmerich, the prolific German director behind some of Hollywood’s most iconic films, including Independence Day and 2012, has built a diverse career spanning over three decades. Throughout his four-decade career, the director’s propensity for churning out an unending torrent of mediocre films has led many to overlook the occasional gem that manages to slip through the cracks, a testament to his enduring talent despite the overwhelming dross.

I’ll always go to bat for “Big Trouble in Little China”, which I regard as a way more cogent attempt at modernizing (Americanizing) than the Spielberg or George Pal efforts, with its much-maligned conclusion echoing that of the original work, accompanied by a winking Y2K-era nod. Despite their individual shortcomings, all four movies fell short of their mark, with the exception being the memorable cranium explosion in ID4, which was elevated by the unique pairing of Smith and Goldblum’s on-screen chemistry.

Independence Day is often misperceived as a groundbreaking catastrophe film, despite being released on the heels of Stargate, which successfully transformed a problematic, ahistorical concept into the foundation of an iconic and long-lasting science fiction franchise. Roland Emmerich, a prolific filmmaker, has managed to craft just two standout films over the past four decades, an achievement that simultaneously highlights his capacity for excellence while underscoring the slim chances of witnessing it again. When he gained possession of my cherished Historic Rome, he crafted something truly sublime? Spectacular. Nicely researched. And dare I suggest that subtle?

This show is undoubtedly a must-watch, making it more than worthwhile for a dedicated marathon session of ten hours. If you can persevere through an initially overwhelming setup, a captivating web of stories unfolds, intertwining the lives of diverse individuals from varying social strata as they navigate the treacherous, gritty cityscape in pursuit of their aspirations. From Domitian, the overlooked prince poised to become Emperor, to Cala, a resourceful Numidian merchant who navigates treacherously to reach the capital of the Roman Empire, driven by an urgent desire to rescue her children from the abyss of punitive slavery and ensure their survival. There exist petty gamblers, burdened by insurmountable debts to settle, street thugs who seize anyone’s wealth to carry out anyone’s dirty work, and gravitating perilously close to their orbit: senators with aspirations towards the imperial purple, the throne now viewed as a stable career path in the aftermath of the Year of Four Emperors.

In this sprawling metropolis, one might find a vibrant tapestry of people from all walks of life, including four distinct “factions” of chariot racing enthusiasts: the crimson-hued, the white-knuckled, the inexperienced thrill-seekers, and the blue-blooded aficionados. Colors that denote their allegiance to various deities exist, including those to Mars, the god of conflict and strife. Zephyr, god of the gentle breeze and atmospheric currents. Notably, the authentic biography of Domitian reveals his penchant for extravagance, as evidenced by the establishment of two additional chariot teams: the purple and gold, which can be seen as an homage to the divine duo governing vitality and wealth. Domitian’s fascination with video games serves as the genesis for the overarching narrative in These About to Die, with the emperor’s entrepreneurial ventures providing the thread that weaves together the collection’s various stories. Domitian leverages video games as a strategic tool to rapidly accumulate personal wealth and cultivate a devoted power base within the city’s confines. Tenax’s unlikely ally, a lowborn individual running the stables and betting operations at the prestigious Circus Maximus, offers a means of upward mobility and expanded influence in Rome’s elite social circles. In the depths of the city’s underbelly, his private fiefdom unfolded like a labyrinth.

If you tune in to Mary Beard’s acclaimed podcast, you’ll likely hear author Robert Harris share his perspective on crafting historical dramas, noting that the key challenge lies in striking a balance between excitement and authenticity – the moment it becomes too thrilling, realism can suffer. When rendering the element excessively realistic, it’s likely to induce a state of utter tedium in those who experience it. Is that really the fight at the core of everything?

The Roman historian Cassius Dio’s portrayal of Domitian in “About to Die” accurately captures the emperor’s reputation as a petulant and vindictive individual. While some details may be open to interpretation, the overall narrative arc feels well-grounded. Roman society remains reeling from an arduous and costly civil war, largely due to its inability to resolve the perennial issue of imperial succession in a timely manner.

Despite the Flavians’ reputation for stability, it’s evident that Rome’s finest days had already passed with the Julio-Claudians, leaving the Flavians as mere caretakers struggling to manage a complex legacy. The analogy of substitute teachers is apt, as they may have been able to navigate basic arithmetic and grammar, but were ill-equipped to handle the intricacies of governing the provinces and securing the grain supply. Amidst a haze of disillusionment, chronic hunger, and listless monotony, the very fabric of society begins to fray, precipitating the sporadic outbreaks of violence and chaos that define this troubled era.

This landscape provides a rich canvas for TV writers, who utilize it effectively: a steady stream of significant events unfolds regularly. As Vesuvius erupted with unprecedented force, it sent pyroclastic flows careening towards Pompeii and Herculaneum, annihilating coastal cities along its path; simultaneously, in Rome, 150 miles northward, the cataclysmic event interrupted a gladiatorial combat, unleashing destruction so intense that buildings crumbled and people were tossed to the ground. What’s that supposed to mean?

Rome’s grandeur is vividly brought to life through stunning computer-generated imagery, its majestic metropolis never having looked more resplendent or vivid on any screen. With an opulence rivalling that of HBO’s Rome, the setting is majestically rendered, showcased through breathtaking aerial vistas of intricately costumed characters and candid glimpses into the lives of the common folk amidst the city’s serpentine alleys. Scorching hot, stained with neglect, every condominium is a cramped and expensive snare to death. It’s genuinely exhilarating! The environment is infectiously vibrant, with distortions from digital camera lenses, laptop graphics, and a writers’ room refracting light through twenty centuries of storytelling’s pricely tapestry.

In “Historic Rome After Dark”, the atmosphere is unexpectedly tranquil, allowing senators to freely roam the streets under the evening’s soft glow. Rome’s ancient streets were notorious for their danger even by day; by night, they became a lawless domain where only the most brazen of ne’er-do-wells dared tread? You were significantly more at risk of dying from a runaway shopping cart careening into the corner and crushing you against the wall than from being stabbed, which seemed an extremely likely occurrence. In 100 BCE, Caesar’s edict banning wheeled vehicles from traversing the city during daylight hours had long been in place, predating the advent of electric lighting. As a result, by nightfall, ancient Rome transformed into a treacherous labyrinth of darkness, where one misstep could prove fatal or lead to disfiguring injury. The present moment shares similarities with daytime, albeit tinged with a subtle blue hue. This, however, is okay: it’s not a documentary; it’s a TV drama. Late-night television is perfect for sneaking around or experiencing thrilling moments. I’m afraid that’s a bit difficult to work with! SKIP

It’s no surprise the Sport of Thrones comparisons emerge at this juncture, since that show notoriously popularized graphic content. At no cost is its popularity justified. In ancient Rome, life was remarkably affordable. Flesh much more so. They’ve often revelled in coarseness, taking a sadistic delight in defacing Pompeii’s ancient walls – a morbid fascination with the city’s ruinous state has left its mark. Comparable in its blithe disregard for violence as that of the present era. Freedom unfurls as spines relax and appendages break free from their bodily constraints. Lions simply eat guys. Despite familiarity with such occurrences, it’s possible to be struck by their significance? Though graphic depictions of intercourse and violence abound, they are treated with a sense of monotonous predictability that belies their sensational nature. That is perhaps most striking in a scene where Emperor Domitian observes three of his preferred male entertainers engaging in intimate relations. What’s occurring is crystal clear, leaving little room for doubt. Located deep within the human form. It’s principally a softcore clip. Even the most captivating aspects of this narrative are eclipsed by a far more mundane reality: not even Domitian can muster genuine enthusiasm for this dullness, his relief palpable as he’s whisked away to attend to matters of greater import.

Rather than a flaw in the present, this reflects a deliberate aspect of the society it portrays from my perspective. The ratio of gratuitous writing to narrative progress in These About to Die sits uncomfortably between the unflinching British dramas where moral crises unfold off-camera, and Spartacus’s notorious bloodbaths, where each episode claims more lives than script pages and features more graphic content than a busy carpet store. Are you aware that you’ve already seen these items? You’re still miffed about rewinding those Outlander episodes? It appears to be desensitized to simulated violence and erotic content, much like the ancient Romans were to real-life brutality. There wasn’t anything else they could point to as a reason for their inactivity, so they relied on the flimsy justification that they simply didn’t have anything better to do. You’ve an Xbox, for disgrace.

So it’s daft. Epic. Foolish. Spectacular. Underwhelmingly explicit, akin to a dry financial report from Flavia. This feels about proper. In all its sweltering, decrepit, and bureaucratic majesty, Historic Rome unfolds with the masterful guidance of someone who understands the art of directing for VFX – an individual unafraid to steer the narrative around a striking image or zoom in on a name scrawled on a desk, leveraging the power of odds to propel the story forward. Given his expertise on the topic and the show’s thematic focus, it’s intriguing that he doesn’t helm every episode where volcanic eruptions like Vesuvius’ explosion unfold.

Ultimately, it’s the film’s underlying humanity that makes These About to Die so compellingly watchable. Sara Martins’ nuanced portrayal of Cala imbues her maternal doggedness with profound depth, serving as a cohesive thread that binds the narrative together; a solitary figure with genuine emotional investment in the story’s outcome. With no reprieve in sight, she craves nothing more than a simple chance to free her young ones from the suffocating grip of the Roman system, which has consumed them whole, leaving her little hope that they’ll escape or thrive under its oppressive rule? Rooted in a fundamental unity, the world of Ancient Rome coheres with remarkable credibility. Domitian’s affection for his brother remained unwavering, despite the intense political competition between them. It serves as a poignant reminder that even the bravest of warriors, those anonymous gladiators who shed their blood in the arena for the entertainment of the crowds, were not just abstract entities, but human beings with loved ones – mothers and sons. We are not so different from these individuals; their flaws merely reflect our own. As do their virtues.

There’s also a significant presence of Welsh individuals, which makes it even more impressive.